https://mailchi.mp/arccopy/fema-dew-sgt-2023-09-11-pt-1-and-2

Read more “SGT REPORT 09/11-2023 PART 1 and 2”Category: CLIMATE EMERGENCY , C.A.P. and WEATHER

2023 09 11 FEMA,-DEWS—KILL-CITIES—-Deb-Tavares–SGT

https://mailchi.mp/arccopy/fema-dew-sgt-2023-09-11

| 2023 09 15 FEMA,-DEWS—KILL-CITIES—-Deb-Tavares–Part-1- |

|

| https://odysee.com/@StopTheCrime:d/FEMA%2C-DEWS—KILL-CITIES—-Deb-Tavares–Part-1-:3 https://rumble.com/v3i6q8q-2023-09-15-fema-dews-kill-cities-deb-tavares-part-1-.html |

FORCED RELOCATION into FEMA’s DESIGNATED “KILL” ZONES

Laser Weapons / DEWS

🔥MAUI -ATTACKED by MORE than YOU THINK💥

https://mailchi.mp/arccopy/maui-attacked-by-more-than-you-think

🔥MAUI -ATTACKED by MORE than YOU THINK💥

Granada Forum – 08/25/2023

with Deborah Tavares

Odysee and Rumble Link Below

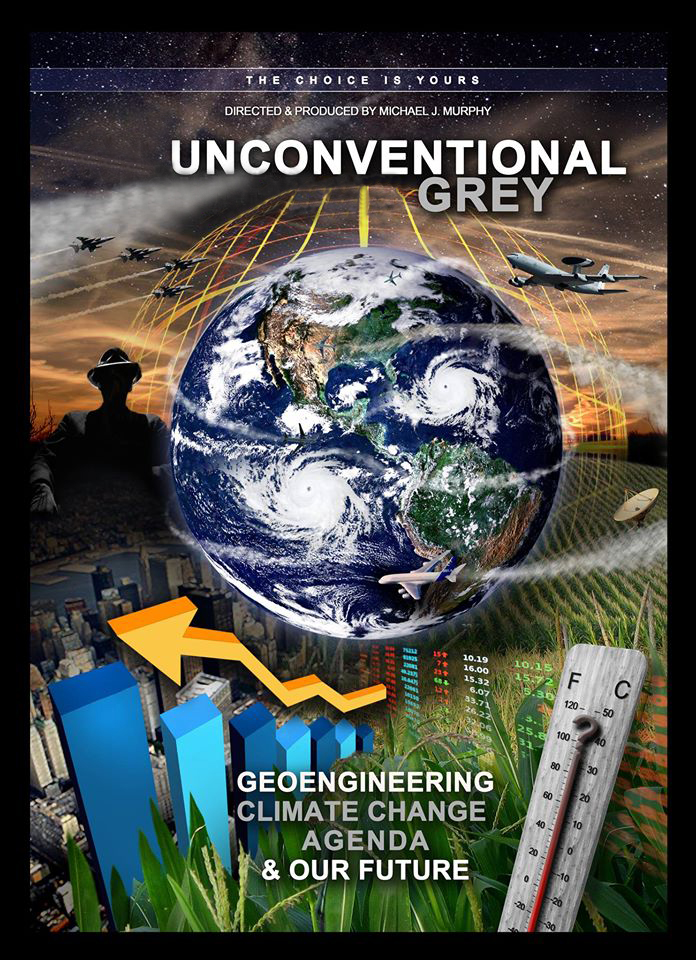

UNConventional Grey

https://mailchi.mp/arccopy/watches-evasive-actions-required-now-9387669

Michael’s “Intended” Artwork for his Film UNconventional Grey

Introducing the Unfinished Third Geoengineering Film of Michael J. Murphy

UNconventional Grey

(links Below)

By Elana Freeland

August 2023

The unfinished third documentary UNconventional Grey by Michael J. Murphy has been missing in action since 2016, the year Murphy had planned to release it. It is his third film of truth-telling about Geoengineering, the other two being

What in the World Are They Spraying?(2010) and

Why in the World Are They Spraying? (2012).

DEW AS WE SAY w/ Deborah Tavares 2023/08/16

Ep. #610: DEW AS WE SAY w/ Deborah Tavares 2023/08/16

Into the Parabnormal – SOMEWHERE BETWEEN PARANORMAL & ABNORMAL

The devastating wildfires in Maui have brought back to the forefront fears of exterminating the population by any means necessary even if that means setting deadly fires and choking off the living.

Jeremy welcomes Deborah Tavares to expose the agenda of weaponized warfare through fires, the use of directed energy weapons and the role of utility companies.

DEW’D Hawaii Torched

https://mailchi.mp/arccopy/murder-chart-9387061?e=2eefef7b3e

DEW’D Hawaii Torched !!!

A “Dry Hurricane from

800 miles away”

Manufactured Climate Change Agenda

Murder Chart

https://mailchi.mp/arccopy/murder-chart?e=034698e356

| MURDER CHARTHow to Get Away with MURDER ☠️ Impact of “Climate Change” on Human Health Unacknowledged USE of Weather Weapons and Lab Created Bioweapons The Road Map to Human Genocideand Death of ALL that is LIVING Colorful Cabal MURDER Chart BELOW Describes How to Legalize MurderJust Call it “Climate Change” Posted byStopTheCrime.net  |

2023-08-01-deborahtavares-water-and-fire

https://mailchi.mp/arccopy/2023-08-01-deborahtavares-water-and-fire?e=2eefef7b3e

| 2023-08-01-DEBORAHTAVARESWATER-AND-FIREDeborah’s newest radio interview on Project Camelot, with Kerry Cassidy. RUMBLE AND ODYSEE LINKS BELOW: https://rumble.com/v3485ft-2023-08-01-deborahtavares-water-and-fire.html https://odysee.com/@StopTheCrime:d/2023-08-01-DEBORAHTAVARES-WATER-AND-FIREfinal1:e  |

HOT WEATHER – We ARE Being Micro Waved

https://mailchi.mp/arccopy/we-r-microwaved?e=034698e356

🆘 WARNING

HOTTER TEMPS INDUCED

BY MICROWAVES

DEADLY HEAT ‘CREATED’ ACROSS

MUCH OF USA, INC. and EARTH, INC.

– MANY COUNTRIES WORLDWIDE.

THIS IS WEATHER WARFARE

Read more “HOT WEATHER – We ARE Being Micro Waved”WIND FARMS -HAZARDS

https://mailchi.mp/arccopy/wind-farms-hazards?e=034698e356

| WIND FARMS -HAZARDS |

| Did You Know About This? UNDER AN IONIZED SKY From Chemtrails to Space Fence Lockdown Indiana, USA and many other locations are DEPLOYING Wind Farms Wind Farms are a Worldwide Deployment Wind Farms and Fracking Well Stems See http://waubrafoundation.org.au and the YouTube “Are Wind Turbines Changing the Weather?” (HowStuffWorks, June 24, 2013). Posted by StopTheCrime.net Visit a wind farm and you will quickly notice that life appears to have fled, which is strange, given how many think of wind farms as “green energy.” While driving through western Ontario, Canadian activist Suzanne Maher noted that what was once beautiful landscape and farmland had been replaced by hundreds of massive, imposing wind turbines. People in homes close to the turbines do not seem to realize they are living inside a power station that operates by creating low-pressure systems, with the blades of each turbine at a 15º angle from the oncoming wind (7.5º / 7.5º) soas to produce a toroid straight-line wind tunnel. Public protests are usually about devaluation of real estate and noise, but the pulsing itself is dangerous to mental and physical health. The infrasound and low frequency noise produce what is being called the wind-turbine syndrome: headaches,sleep problems, night terrors, learning disabilities, ringing in the ears(tinnitus), mood swings (irritability, anxiety), concentration and memory problems, and equilibrium issues like dizziness and nausea. From the Mariana islands to Hawaii (through the Kwajalein Atoll), a line of transmitters fires northeast in a repetitious pulse—an invisible wall of radio waves all the way to Alaska that creates a funneling effect. Fire radio frequency into a front that’s been “seeded” with aluminum nanoparticles and a plasma-dense field arises, while the pressure wall off of Mexico acts like the bumper on a billiard table to roll the weather system north along the California-Oregon coastline to Vancouver Island and the jetstream ready to be pushed east and south through Wyoming and the Dakotas and into Kansas where NexRad and wind farm pulses will kick in to build high pressure for tornadoes, superstorms, and floods.[1] Wind farms and hydraulic fracturing (fracking) wells are separated by exactly 300 miles, like GWEN towers, then calibrated together. Fracking wells provide grounding points for wind farms while creating new faultlines for earthquake terraforming. According to Billy Hayes “The HAARP Man,” the brine in the well heads of all new wells is treated with absorbents like the aluminum oxide and barium oxide being laid in chemtrails. A directional explosive is then packed into the well to create perforations in the casing for about 20 feet out so the acid seeps down with the brine mix on top. This “re-dosing” must penetrate the casing because without water, it will float to the top of the well. Wind turbines and oil well stems have the same resonant length of 1,282 feet. Each rotation of a wind turbine gives off a powerful static charge. In fact, every time the turbines pulse at 2.95 Hz in 1-nanosecond pulses, the liquid mixture at the well head jumps 20 pounds up and 20 pounds down 3X per second like a hammer.This is called “thumping.” The discharge of the wind farms occurs in an arc at a certain length and a certain pulse that resonates with wells tuned to 2.95Hz. Put your hand on the casing and feel it twitch, like it’s alive. Both wind farms and fracking well stems have a part to play in the Space Fence infrastructure, along ionospheric heaters, NexRads, cell and GWEN towers, etc. It is because of how they pulse together that nations like Scotland[2] and states like Oklahoma[3] won’t be allowed to ban for long the unconventional practice of fracking. [1] See http://waubrafoundation.org.au and the YouTube “Are WindTurbines Changing the Weather?” (HowStuffWorks, June 24, 2013). [2] ClaireBernish, “Scotland Just Banned Fracking Forever.” Elle, August 6, 2016. [3] EmilyAtkin, “Fracking Bans Are No Longer Allowed in Oklahoma.” Climate Progress, June 1,2015. Elana Freeland, MA THE GEOENGINEERING TRILOGY: Geoengineered Transhumanism: How the Environment Has Been Weaponized by Chemicals, Electromagnetism & Nanotechnology for SyntheticBiology (2021) Under An Ionized Sky: From Chemtrails to Space Fence Lockdown(2018) Chemtrails, HAARP, and the Full Spectrum Dominance of Planet Earth (2014) Sub Rosa America: A Deep State History series,2nd Ed. 2018 Blog site: elanafreeland.com Rudolf Steiner: “In our time, the most important thing is to bring forward truths – put plainly, to give lectures about truths. What people then do about this is up to their freedom. One should go no further than to lecture on, to communicate truths. Whatever consequences there are should follow as a free decision, thus as consequences follow when decisions are made out of the impulses one has on the physical plane. It is exactly the same in the case of things that can only beguided from the spiritual world itself.” – Secret Brotherhoods and theMystery of the Human Double, 7 Lectures in St. Gallen, Zurich and Dornach,1917 |