WASHINGTON, February 2, 2021 — The “second wave” of the coronavirus pandemic has placed much blame on a lack of appropriate safety measures. However, due to the impacts of weather, research suggests two outbreaks per year during a pandemic are inevitable.

Though face masks, travel restrictions, and social distancing guidelines help slow the number of new infections in the short term, the lack of climate effects incorporated into epidemiological models presents a glaring hole that can cause long-term effects. In Physics of Fluids, from AIP Publishing, Talib Dbouk and Dimitris Drikakis, from the University of Nicosia in Cyprus, discuss the impacts of these parameters.

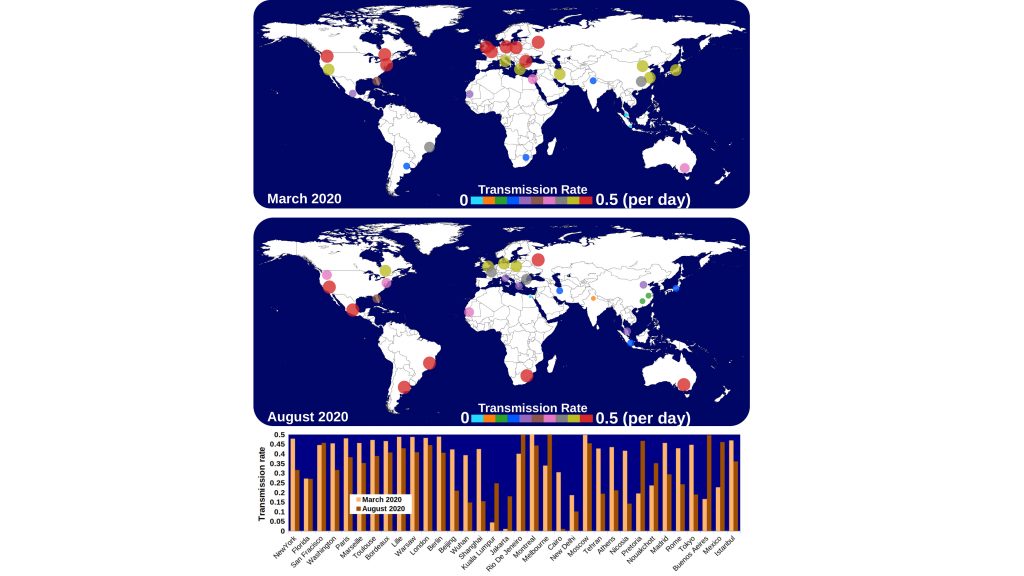

Typical models for predicting the behavior of an epidemic contain only two basic parameters, transmission rate and recovery rate. These rates tend to be treated as constants, but Dbouk and Drikakis said this is not actually the case.

Temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed all play a significant role, so the researchers aimed to modify typical models to account for these climate conditions. They call their new weather-dependent variable the Airborne Infection Rate index.

When they applied the AIR index to models of Paris, New York City, and Rio de Janeiro, they found it accurately predicted the timing of the second outbreak in each city, suggesting two outbreaks per year is a natural, weather-dependent phenomenon. Further, the behavior of the virus in Rio de Janeiro was markedly different from the behavior of the virus in Paris and New York, due to seasonal variations in the northern and southern hemispheres, consistent with real data.

The authors emphasize the importance of accounting for these seasonal variations when designing safety measures.

“We propose that epidemiological models must incorporate climate effects through the AIR index,” said Drikakis. “National lockdowns or large-scale lockdowns should not be based on short-term prediction models that exclude the effects of weather seasonality.”

“In pandemics, where massive and effective vaccination is not available, the government planning should be longer-term by considering weather effects and design the public health and safety guidelines accordingly,” said Dbouk. “This could help avoid reactive responses in terms of strict lockdowns that adversely affect all aspects of life and the global economy.”

As temperatures rise and humidity falls, Drikakis and Dbouk expect another improvement in infection numbers, though they note that mask and distancing guidelines should continue to be followed with the appropriate weather-based modifications.

This research group’s previous work showed that droplets of saliva can travel 18 feet in five seconds when an unmasked person coughs and extended their studies to examine the effects of face masks and weather conditions. The authors are incorporating the previous findings into their epidemiological models.